Recently in the US, farmers have increasingly used fungicides on corn crops with a noticeable yield increase. There is significant corn (maize) acreage in Europe, but hardly even any research on fungicides. Recently, a European researcher experimented with fungicides and discovered the great potential of using fungicides for this overlooked problem.

“Since 2008, fungicide trials have been carried out by both the Danish advisory service (Knowledge Centre for Agriculture) and University of Aarhus to test the impact of fungicides on control of leaf diseases. In several of the trials, significant levels of diseases have occurred and significant yield responses have been obtained.

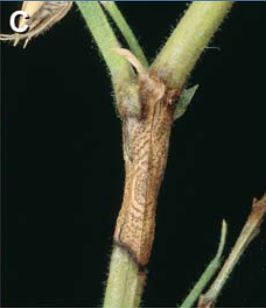

In 2009, a severe attack of northern corn leaf blight (E. turcicum) developed and 50% yield increases were accomplished from fungicide treatments in a number of trials. In 2011, a severe and early attack of Eyespot (K. zeae) developed in several trials and in that season yield increases between 50 to 60% were also achieved in grain maize crops in fields with minimal tillage with maize as the previous crop.

Based on good efficacy trials, the first fungicide epoxiconazole plus pyraclostrobin (as Opera) was authorized in Denmark for control of the leaf diseases in maize between detection of 3rd node and the tassels appearing at the top of the stem (BBCH GS 33-51).

For scientists, advisors and farmers, it was a surprise that yield reducing leaf diseases could play such a major role in the production of maize. When looking around Europe for information on this subject, we were slightly surprised that very little information on the use of fungicides was available. When looking around we also realized that in many countries no fungicides are authorized for control. Looking across to the US, which has long experiences with foliar diseases, there seem to be more knowledge available on disease management, including experiences from use of fungicides.”

Author: Jorgensen, L. N.

Affiliation: Department of Agroecology, Aarhus University, Denmark

Title: Significant yield increases from control of leaf diseases in maize – an overlooked problem?!

Source: Outlooks on Pest Management. August 2012. Pgs.162-165.