Michigan is the leading producer of tart cherries in the United States, with annual yields of 90.9-127.3 million kg, which represents approximately 75% of the total US production.

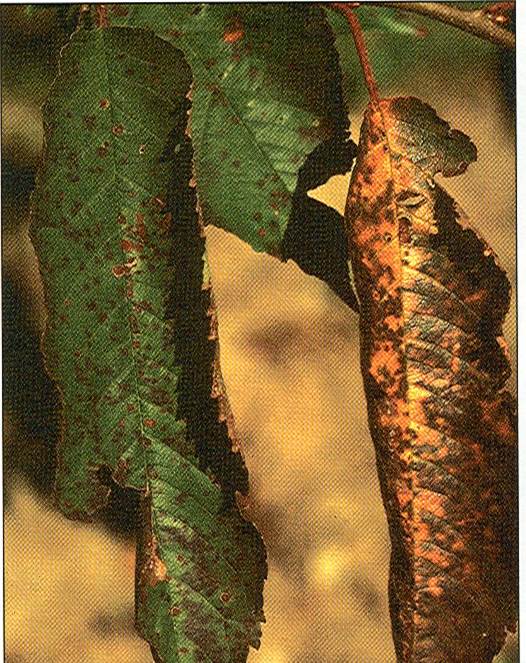

Leaf spot is the most important fungal disease of cherry trees in Michigan. The appearance of numerous spots on the leaf is usually followed by rapid yellowing and dropping. In experiments, it has been demonstrated that poor control of leaf spot can result in 72% of the tree branches dying during the winter months.

“Cherry leaf spot (CLS) is the most damaging pathogen of tart (sour) cherry trees. All commercial tart cherry cultivars grown in the Great Lakes region of the United States are susceptible to CLS, including the widely grown cultivar Montmorency, which accounts for more than 90% of the tart cherry acreage in Michigan. Left unmanaged, CLS infection causes significant defoliation by mid-summer, resulting in fruit that is unevenly ripened, soft, poorly colored and low in soluble solids. Early defoliation also delays acclimation of fruit buds and wood to cold temperatures in the fall, increases tree mortality during severe winters and reduces fruit bud survival and fruit set the following year.

The almost complete reliance of the tart cherry industry on the cultivar Montmorency has driven a strict dependence on fungicides for disease management. Typically, 6-8 fungicide applications per year are required, beginning at petal fall and continuing through to late summer after harvest.”

Author: Proffer, T. J., et al.

Affiliation: Michigan State University

Title: Evaluation of dodine, fluopyram and penthiopyrad for the management of leaf spot and powdery mildew of tart cherry, and fungicide sensitivity screening of Michigan populations of Blumeriella jaapii.

Source: Pest Management Science. 2013. 69:747-754.