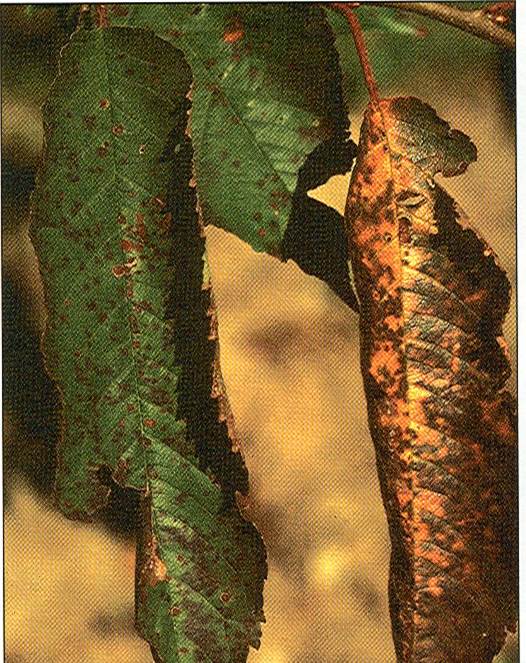

Alternaria late blight infects both leaves and fruit, causing early defoliation, severe brown-black stains on the shells and mold contamination of the shells and kernels. Other damage from Alternaria includes poor flavor and possible mycotoxin contamination. Without fungicide applications, alternaria would reduce California pistachio production by 30-50%.

“Alternaria late blight (ALB), caused by Alternaria alternata, A. tenuissima, and A. arborescens, is now considered the most destructive disease of pistachio in California. The disease affects foliage and fruit and is an annual production concern for pistachio growers. On foliage, it can be recognized by the development of large necrotic lesions, and multiple, expanding lesions eventually consume the whole leaf. The lesions are black in the center due to the production of many spores and are surrounded by a chlorotic halo. Under optimal conditions for the disease, the fungus can defoliate a tree in late summer and autumn. On fruit, it is characterized by small necrotic lesions surrounded by a red halo. These are located on the hull of immature nuts. When the nuts develop, one or two lesions can penetrate and decay the hull, resulting in shell staining of the nut underneath. The staining of the shell and colonization of the kernel result in a reduction of the nut quality. Although cultural practices such as irrigation management and pruning to increase air movement and decrease air humidity in the orchard can help reduce ALB, the use of multiple fungicide applications is essential to achieve adequate disease control.”

Authors: Avenot, H. F., et al.

Affiliation: Department of Plant Pathology, UC-Davis.

Title: Sensitivities of Baseline Isolates and Boscalid-Resistant Mutants of Alternaria alternata from Pistachio to Fluopyram, Penthiopyrad, and Fluxapyroxad.

Source: Plant Disease. 2014. 98[2]:197-198.