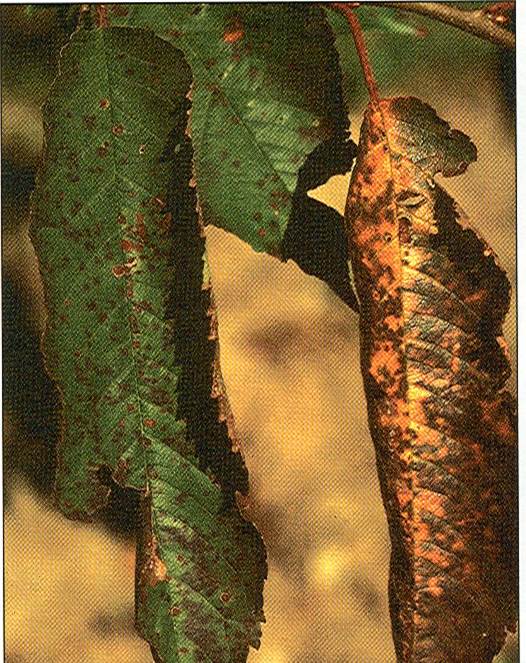

Fusarium Head Blight (FHB), also known as scab, is a destructive disease of wheat and other small grains. In the spring, ascospores and/or conidia are released from crop residues and are spread by wind or splashing water. They land on wheat heads and during wet, warm weather they germinate and infect glumes, flower parts, or other parts of the head.

In addition to lowering grain yield and quality, F. graminearum produces mycotoxins, primarily the trichothecenes deoxynivalenol (DON), nivalenol (NIV) and T-2 toxin. …These mycotoxins are harmful to humans and livestock. In North America, DON, also known as vomitoxin, is the most common and economically important mycotoxin found In Fusarium-infected wheat. …Grain with high concentrations of DON often is discounted or rejected at the elevator, which exacerbates the losses incurred by the farmer.

“In the U.S., a less than desirable number of current commercial wheat cultivars have moderate resistance to FHB and this resistance can be overwhelmed in years with high disease intensity. Fungicides are often applied to control FHB when favorable conditions for disease development are forecast.

Over the last two decades, there has been considerable improvement in the effectiveness of fungicides in controlling FHB and DON. This improvement is attributable in part to improved fungicide chemistries and greater knowledge gained through research on fungicide application rates, timing, and technology.

The best approach to managing FHB is to integrate available management strategies. Research has shown that integrating cultivar resistance with fungicide application can be effective management strategy for FHB.

Availability of moderately resistant cultivars and new fungicide chemistries coupled with improved fungicide application technology has led to greater farmer adoption of an integrated strategy in the management of FHB and DON.”

Authors: Wegulo, S. N., et al.

Affiliation: Department of Plant Pathology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Title: Integration of fungicide application and cultivar resistance to manage fusarium head blight in wheat.

Source: InTech. Fungicides – Showcases of Integrated Plant Disease Management from Around the World. Available at: http://www.intechopen.com/books/fungicides-showcases-of-integrated-plant-disease-management-from-around-the-world